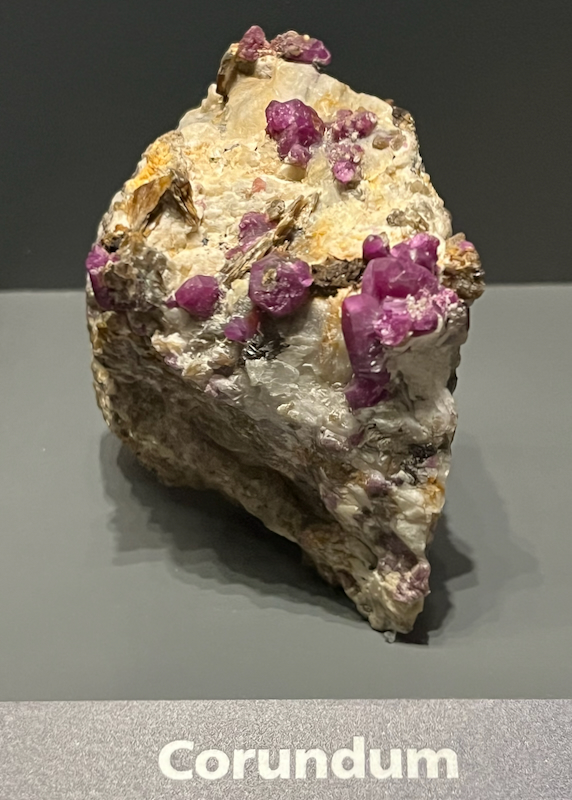

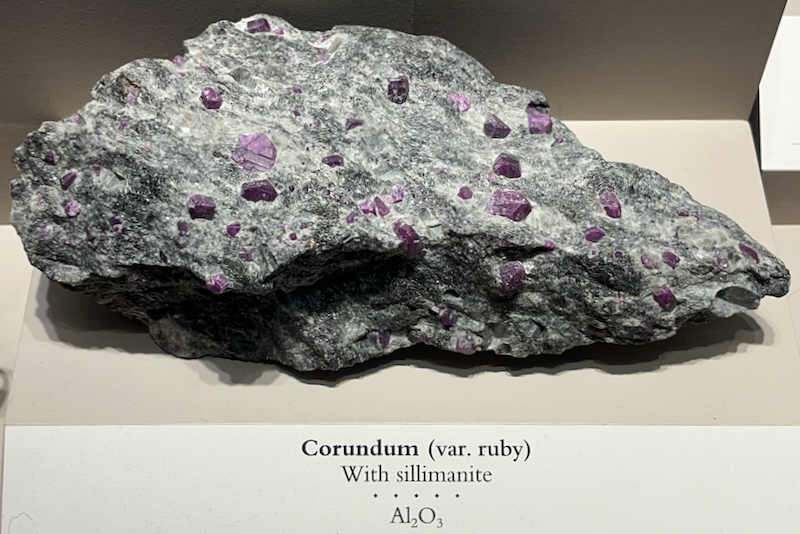

Ruby

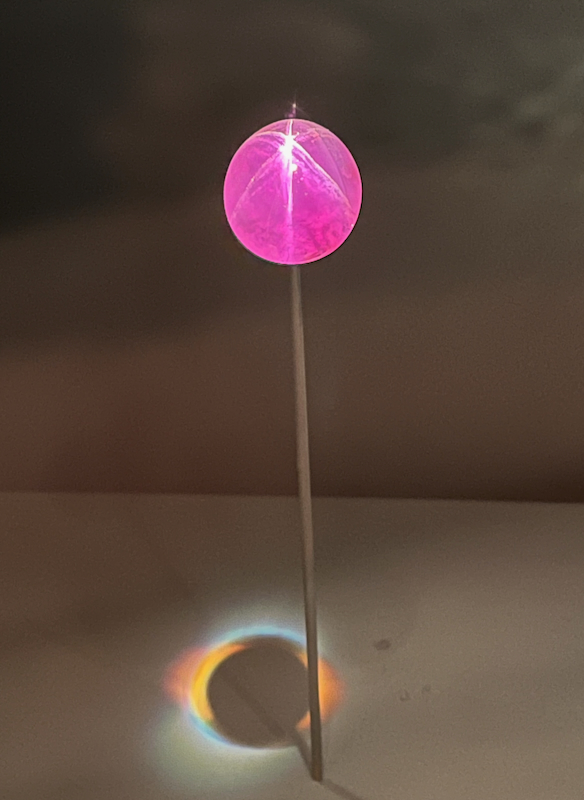

As mentioned in the general information, in the Middle Ages the name ruby was meant to just be for red corundum, but for a long time, no one could tell red corundum from other minerals, such as red spinel. As a result, some large, beautiful “rubies,” such as some of the ones in the British crown jewels, aren’t really rubies after all! The red color of the “best” rubies is not the standard “primary” red you might think of. Instead, it’s a pinkish purplish red that some people refer to as “pigeon blood”—yuck! Tiny amounts of several different minerals determine a ruby’s color. Chromium is the main influence, and the amount that’s in the ruby can make it pinkish, if a small amount, or deep red, if a large amount. Iron can make a ruby more brown or orange looking, and titanium and vanadium can have an effect too. Rubies can be totally opaque, which makes them much less expensive, but it’s the clear ones that are used as gemstones for jewelry. Coming in at a 9 on the Mohs hardness scale, rubies are just below diamonds in their hardness, so they’ve had many practical uses too. If you’re interested in buying an analog watch, such as one from Switzerland, the ad might say the watch has “a 15-jewel movement.” Often, those “jewels” are tiny perfectly rounded rubies that are hard enough to last for years as part of the tiny machinery inside the watch. With the same idea, rubies have also been used for turntable needles to play records. Taking advantage of their toughness in a different way, crushed up rubies are also used as a special kind of “sand” in some sandpaper.

| Formula | Group or Type | Shape | Hardness | Specific Gravity | Streak | Luster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3 | Corundum | Hexagonal | 9 | 3.9–4.1 | White | Adamantine to waxy |