The Science Behind Rocks and Minerals

One of the best things about the hobby of rock collecting is that there’s a lot to learn, and a lot of what you can learn is, well, really cool! Rocks and minerals are all around us, on the ground, by the side of the road, in mountain ranges, but also in the ring on your finger, in the teeth in your mouth, in your cell phone, in your salt shaker, and just about everywhere else. So, yeah, if you like discovering cool things about the world around you, rocks and minerals is a great place to be.

What’s the Difference?

When we’re talking about rocks and minerals, one of the first questions that might pop up is “Okay, what’s a rock and what’s a mineral?” Well, in day-to-day life, just walking around, if you find a hard object on the ground that’s not wood or a piece of litter, you’d probably just call it a rock, even if it was a piece of pure quartz. If you wanted to get technical, though, you’d call some of these hard objects rocks and others minerals. But which is which? What’s the difference?

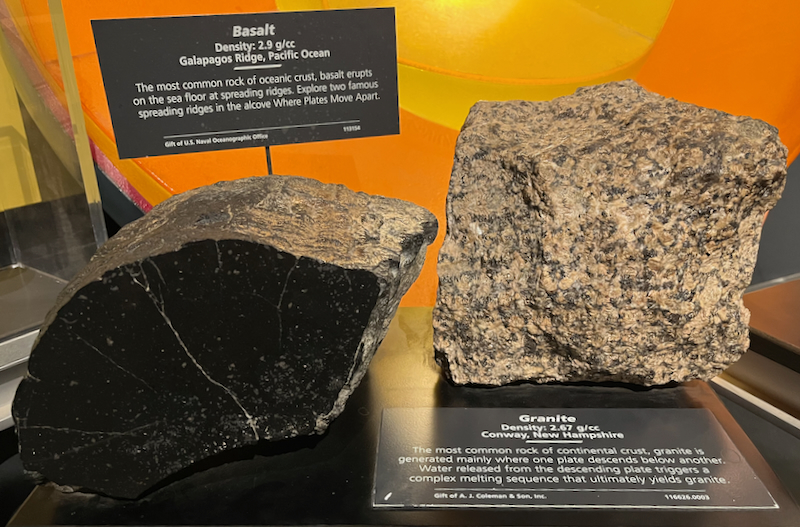

A mineral is a (almost always) solid substance that has a specific formula for what it’s made of—like the ingredients in a recipe. For example, a piece of pure quartz, which has the formula SiO2, would be made of the elements silicon (Si) and oxygen (O) and would be considered a mineral. A rock, on the other hand, also a solid substance, is made of two or more minerals. For example, granite, a very strong type of rock used for building buildings, is made of the minerals quartz, mica, and feldspar. For another example, limestone, which is a good kind of rock to find fossils in, is mostly made of calcite, but with several other minerals mixed in.

All that said, still, most people who collect minerals, rocks, or both just lump everything together and call them all “rocks” when they’re talking about them. It’s a lot easier than always spelling out “rocks and minerals,” “rocks” is shorter than “minerals” and has a very satisfying “rocky” sound to it, and it’s less formal. So on this site, if we talk about rocks when we’ve just been describing a mineral, it’s not because we forgot it’s a mineral, we’re just doing what comes naturally for most people who love…rocks (and/or minerals).

Back to the science, now that you know what minerals and rocks are, what kinds of rocks and minerals are there? We could make a really long list for both rocks and minerals, but that could get way out of control really quickly if we got too specific, so let’s start with the big picture. Because there aren’t as many rock types as mineral types, let’s talk about rocks first.

Types of Rock

Rocks can be broken up into groups (or, if you have a hammer and a chisel, into pieces) by how they’re formed or what they’re made of. The easier way to remember is how they’re formed, so let’s focus on that. Three different types describe how they’re formed: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary, and some people add a fourth type: meteorites, for rocks that are truly “out of this world.”

Igneous

Igneous rocks are rocks that are produced from magma, which is a bunch of totally melted together rocks and minerals in liquid form deep underground. Igneous rock can form if the magma cools off and becomes solid while it’s still underground, or if it pours out on the earth’s surface from a volcano or through a crack as lava, then becomes solid above ground. Granite is a common underground igneous rock, whereas a common above-ground igneous rock would be basalt. What’s the difference between lava and magma? They’re the same thing, but lava is magma that has erupted and isn’t underground anymore.

Metamorphic

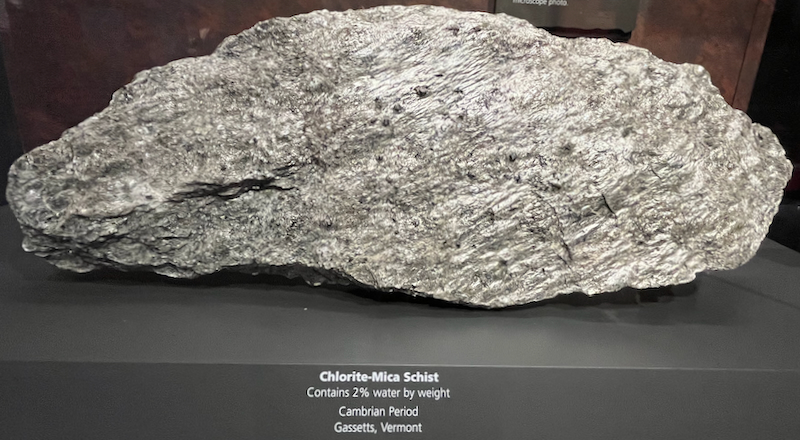

Metamorphic rocks are formed by heat and pressure underground, and that can happen a couple different ways. In one standard situation, you have some existing rock that is buried very deeply so it has a lot of pressure squeezing it from all the heavy rock above it, and at the same time it’s very hot down there, either from nearby magma or from just being closer to the earth’s hot core.

Another high-pressure situation happens with what’s called “plate tectonics.” As you may have heard, all of our continents—North America, South America, Africa, etc.—are very slowly sliding around the earth like giant stone rafts (or plates). We don’t usually see it, but much of the time, the edges of the rafts are running into each other. When they do, the edge of one raft will start sliding up slightly, and the edge of the other will start sliding down. These rafts are huge and heavy, so when they slide under/over each other, it creates a lot of pressure, and as they rub together, the friction between them creates heat too.

Whatever way the pressure and heat happen, they can cause metamorphosis, which means “changing form,” of the rock in the area of the pressure and heat. Sometimes the change can be pretty simple—it basically just compresses the rock and makes it harder. But often the combined pressure and heat can cause some minerals inside the rock to change into other minerals, and sometimes minerals from the surrounding rock will seep into the rock that’s being squeezed/heated, and that will make it change even more. One common metamorphic rock is marble, which is limestone or dolomite that has been changed by pressure and heat into, actually, a much better looking rock.

Sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are made up of small particles that form layers over a long period of time. If you stir up some mud at the bottom of a pond, the water will get all cloudy for a while, but then eventually it will get clearer as the particles of dirt from the mud settle back down. Those particles are sediments. A large amount of sediments are brought into ponds, lakes, and oceans by streams and rivers. If millions of years pass, the layers can stack up into an extremely thick deposit, and eventually it can start hardening into rock.

The sediments in sedimentary rock aren’t always from floating dirt particles, and they don’t always come from water. For example, the particles can be sand from a desert or from breaking up rocks into tiny pieces as they bang against each other in the ocean or a river or under a glacier. They can also be pieces of seashells, coral, and other sea creatures that create sediment that’s mostly calcite, since that’s what those pieces are made of. Aside from erosion by water, wind can erode rocks and wear off tiny pieces that become sediments too.

When enough of these sediments pile up, the stack of layers can start forming rock from the pressure of the sediment layers above on the layers below. It’s also possible for other rock–such as a lot of rock from a volcanic eruption–to cover the layers of sediment and squeeze them with its weight. In either case, at the same time, some dissolved minerals, such as silicon, may spread into the sediment layers and help to tie the particles together so they solidify better into rock.

You may not be surprised that sandstone is a sedimentary rock that’s made up of sand particles. Shale is another kind of sedimentary rock, and it’s made up of mud particles. And if a lot of organic matter—trees, ferns, dinosaurs—was left in the mud and decayed there, it might be “oil shale,” which contains oil, like the kind we use to make gasoline. Finally, remember those particles from sea creatures? They’re the main material that makes up limestone, with a dash of those dissolved minerals we mentioned mixed in.

Meteorites

As mentioned, some people like to add a fourth type of rock to make sure rocks that fall out of the sky don’t feel left out. Meteorites are pretty much any natural solid objects from space that hit the ground here on earth. (Falling space junk like rocket pieces and old satellites doesn’t count.) They can range in size from a pinhead or smaller—a “micrometeorite”—to as big as a bus or larger. Whatever its size, a meteorite is just a piece of rock, or sometimes of pure metal, that is what’s left after a bigger piece falls through our planet’s atmosphere. (The fall through the atmosphere usually burns up a lot of it.)

© Kevin Downey/Well-Arranged Molecules

Meteorites can be from all different sources. Things in space are often smashing into each other because of gravity, stars exploding, the expansion of the universe, etc. And sometimes when they do, chunks of rock break off and go flying into space.

Although some people call this a fourth type, at least some of the rocks we’re talking about were originally formed…somewhere(!)…in one of the first three ways. Careful analysis of meteorites that have been found on Earth has shown that some of them come from the moon, some from Mars, and some even from chunks that were left over when the Earth formed into the globe it is today. Other meteorites may have come from other planets/moons, including distant ones we don’t know about. As a result, there’s a good chance that a meteorite is from a planet or moon, where it originally formed in an igneous, metamorphic, or sedimentary way.

It’s true that we didn’t include “from a star exploding” as one of the first three types, so maybe that could be its own special type, but it would be a mistake to say no meteorites originally formed in the first three ways.

Photo © NASA. X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Infrared: NASA/STScI; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/J. Major

Types of Minerals

Depending on who you ask, there are roughly 6,000 or 10,000(!) different known minerals, and more are being discovered as we speak. With that many minerals, you can probably guess that there are also a lot of different types of minerals.

What’s a Gem, Gemstone, Jewel, Precious Stone, or Crystal?

Before we launch ahead, we should probably talk about a few different words you might hear in place of the word “mineral.” Some of the most common words would be gem, gemstone, jewel, precious stone, and crystal. Most of these words are referring to minerals that are really nice quality—they’re really clear/transparent (see-through) or translucent (light passes through them); they have bright, vivid, or “saturated” (concentrated or intense) color; and/or they have really well-formed crystals that grew in a way that they have natural facets. If any of these words are used instead of “mineral,” it usually means they’re more valuable and/or are used in jewelry. Of course, some people just call any mineral a “stone” or a “rock,” even if it’s really valuable, like a diamond in a diamond ring for example—“Nice rock!”

The Famous Dana Classification System

To try to make sense of the wide variety of minerals, way back in 1837 an American scientist named James Dwight Dana created a system to classify the different minerals into, well, classes. Most of Dana’s classes were based on the important elements that the minerals were made up of.

We talked about quartz in the What’s the Difference section and how it’s made of silicon and oxygen. Well, one large and important class is called “Silicates,” because they all have silicon in them, and that class includes quartz. (Actually, the class was called “Silicates and germanates” and included minerals that have the element germanium in them, but germanium is so rare that people eventually just started saying “Silicates.”)

Another example of an important class is “Sulfides and sulfosalts,” because all its minerals have sulfur in them. One well-known “Sulfide” is pyrite, also called “fool’s gold” because it looks like gold but isn’t, and it has the formula FeS2. It’s a combination of iron (Fe) and sulfur (S).

Most of the time, you don’t need to know what class a mineral is in, but sometimes it can help, because minerals in the same class can have similar qualities. For example, if you have a mineral you know is a silicate and another that’s a carbonate, and you spill vinegar on both of them, the silicate mineral will probably be fine, while the carbonate might start dissolving. If you just like rocks as a hobby, it’s not important to remember all the classes or anything, but it’s useful to have an idea of what they are, in case someone uses them later, then you’ll know what the heck they’re talking about. We’ll just quickly list them here.

Dana broke things up into a total of nine classes:

- Native elements—Minerals that are only made up of themselves, or, more specifically, their element, such as gold, silver, and copper

- Sulfides and sulfosalts—Minerals containing a specific type or amount of the element sulfur

- Oxides and hydroxides—Minerals containing a specific type or amount of the element oxygen, or of combined hydrogen and oxygen (hydroxide)

- Halides—Minerals containing the element halogen

- Carbonates, nitrates, and borates—Minerals containing the element carbon, nitrogen, or boron

- Sulfates, chromates, and molybdates—Minerals containing a different type or amount of the element sulfur (different from #2 above), or the element chromium or molybdenum

- Phosphates, arsenates, and vanadates—Minerals containing the element phosphorus, arsenic, or vanadium

- Organic minerals—Substances that were originally from plants or animals, such as amber, which is hardened tree sap

- Silicates and germanates—Minerals containing the element silicon or germanium

Of course, because Dana came up with those classes a long time ago, other people have created newer systems since then that use their own classes. But Dana must not have done a bad job, because the other people’s classes look suspiciously similar to Dana’s classes!

Like the three types of rocks, these nine classes of minerals give you the big picture. If you’re going to tell 6,000 or 10,000 minerals apart from each other though, you need the super close-up picture. The super close-up of any mineral is its formula.

The Formulas for Minerals

What’s a formula? When we’re talking about minerals, basically it’s a recipe that tells the mineral’s ingredients. What’s the most well-known formula in the world? I’ll give you a hint—it’s water. Yes, that’s right, H2O. What exactly does that mean?

Well, there’s this chart called the periodic table that was originally created around 1870, and its goal was to list all the different elements (hydrogen, oxygen, sulfur, silicon, etc.) in an organized way. To keep the table from getting too big, each element’s name was shortened to one or two letters. For example, hydrogen became “H,” oxygen became “O,” sulfur became “S,” and silicon became “Si” (with the ‘i’ added so it wouldn’t get confused with sulfur). Have a look at the table to see how it lists/organizes all the elements.

Weird Element Abbreviations

If you’re not a chemistry professor, when you look at a copy of the periodic table that just shows abbreviations, you probably won’t know what a lot of them mean. Actually, the first time you look at it, you might not know any of them! But if you’ve gotten this far on the science page, you at least know what H, O, S, and Si mean. As you read further, you’ll learn more of them and see that most of them make sense–nickel is Ni, aluminum is Al, helium is He–but some of them might not…at first.

What are Au, Cu, Pb, Hg, and other abbreviations that don’t seem to match the name of the element they’re abbreviating?

Well, back in the days before the periodic table was invented, the official language of learning and science in “The Western World” (Europe, Russia, etc.) was Latin. When it came time for this guy Mendeleyev to create the table, many of the elements he knew about–a lot of elements hadn’t been discovered or named yet–had been given Latin names. Many of the names were in Latin because the elements were discovered during or before the Roman Empire, while some others were discovered more recently but got Latin names just by tradition.

It’s a little inconsistent, but as the periodic table was updated over the years, a bunch of elements kept their abbreviations based on their Latin names instead of their English names. A big part of that was because the people working on the table were running out of initials! For example, with silicon and silver, only one could be Si. Silicon won that contest, and silver instead got Ag.

As you’ll see, some of the most common and important elements are the ones whose abbreviations match their Latin names. Here’s a little element name etymology for you:

| English Name | Latin Name | Abbreviation |

| Silver | Argentum | Ag |

| Gold | Aurum | Au |

| Iron | Ferrum | Fe |

| Copper | Cuprum | Cu |

| Mercury | Hydrargyrum | Hg |

| Lead | Plumbum | Pb |

| Tin | Stannum | Sn |

| Sodium | Natrium | Na |

| Potassium | Kalium | K |

Keeping it simple, water is two parts hydrogen (H2) and one part oxygen (O). The little ‘2’ or other number stuck on the right side tells you how many parts are from that element. (They don’t bother adding the number ‘1’ if there’s just one.) But wait, (liquid) water isn’t a mineral! Okay okay, liquids and minerals can both have formulas, and so can gases—maybe you’ve heard of CO2 (carbon dioxide)? That’s a gas.

If you’re lucky, you get a really nice, simple formula. For example, the formula for diamond is just “C.” Diamond is one of very few minerals that’s just made of one thing, carbon in this case. You may have already seen quartz’s fairly simple formula if you read the What’s the Difference section—it’s SiO2, and that’s made of just two elements, silicon and oxygen.

Sometimes, though, you have bad luck, and you get stuck with a formula like the one for elbaite, which most people call tourmaline. Okay, prepare yourself: Na(Li1.5Al1.5)Al6(Si6O18)(BO3)3(OH)3(OH). Figure that one out! As they say in the business world, “That is beyond the scope of this report,” but you can at least see that there’s some Na, Li, Al, Si, B, O, and H in it, or sodium, lithium, aluminum, silicon, boron, oxygen, and hydrogen. It’s complicated.

As with the mineral classes, you don’t have to memorize the periodic table, but it can help to have an idea what formulas look like and the most common elements you’ll see in them. For one thing, it’ll help you see when two minerals might be similar in some way.

Here’s a very practical example if you like to go out and collect rocks. Say you join a mineral club and get to go on a field trip to a mine. If the mine owner says you can find tourmaline there, and you know from the ridiculous formula above that tourmaline has lithium in it, that could help you know that you might also find beautiful purple lepidolite there (with its own complicated formula, K(Li,Al)3(Al,Si,Rb)4O10(F,OH)2), since it has lithium in it too.

What’s Important About Mineral Names?

Before you know a mineral’s formula, you usually know its name. Long before anyone thought of creating formulas or the periodic table, a thousand or more years before, they were giving minerals names.

In the (very) old days, minerals were named in simple ways. For example, in the middle ages, the mineral name “ruby” was meant to be the word for a specific mineral (red corundum). But they didn’t realize that other minerals could form red gemstones too. As a result, a lot of gemstones that were not technically ruby got called ruby—for example, red spinel or red garnet. As another example, according to Mindat, when the Greeks found quartz crystals, they originally created their word for “crystal” from their word for “ice” based on thinking the clear quartz was permanently frozen ice. Surprisingly, a couple thousand years later, some people still call quartz “rock crystal,” even though lots of other “rocks” (minerals) form crystals.

Zooming ahead to more recent times, minerals are mainly named based on their characteristics, like color or shape; what elements are in them; who found them; where they were found; or to make some rich person or famous scientist happy. Once you start digging into minerals more, you’ll probably notice that many of their names end in “ite,” which means roughly “is this way (usually or always).” Let’s look at some examples.

Actinolite is a mineral found in various places, including in and around talc or asbestos mines. Often when you find it in crystal form, the crystals look like rays shooting out from a center point, like the rays of the sun or the feathers in a turkey’s tail. Its name is based on the Latin word for “ray”…with “ite” stuck on the end, so it basically means “mineral that usually has ray-shaped crystals.”

Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com – CC-BY-SA-3.0, Actinolite-247712, CC BY-SA 3.0

Vanadinite is a very cool looking orange mineral you’re most likely to find in lead mines and other metal mines. It’s usually a reddish orange, and the crystals are often these randomly stacked hexagons, but it gets its name from having the element vanadium in it. Its name means simply “mineral that has vanadium in it.”

© Kevin Downey/Well-Arranged Molecules

Wavellite usually forms in green or yellow spheres, but if one of the spheres splits, you can see it’s actually made of tightly packed rays (like actinolite, but more extreme) that radiate out from the center of the sphere. That said, it’s not named for yellow, green, sphere, or rays, it’s named after the naturalist (amateur scientist interested in nature) William Wavell, who first found it. Its meaning would be something like “mineral that’s like the one Wavell found.”

© Kevin Downey/Well-Arranged Molecules

Vesuvianite is usually found with other “calc-silicate” minerals, as pro rockhounds say, such as diopside and grossular garnet. That means the minerals can have both calcium and silicon in them, and that combo often causes attractive crystals to form that are worth collecting. But even more impressive is where this mineral was first found: the volcano known as Mount Vesuvius in Italy! It’s “the mineral that’s like the one you can find on Mt. Vesuvius.”

© Kevin Downey/Well-Arranged Molecules

First Found: When and Where a Mineral Was Discovered…Kind Of

When you’re reading the general science information or the specific mineral descriptions on this website, or looking at other websites about minerals, you’ll often learn when or where a mineral was first “discovered” or when it was “named.” At the same time, you may have heard that even prehistoric humans tens of thousands of years ago would collect pretty rocks and minerals. Archaeologists know this, because they have found the rock collections of those primitive humans!

So when we talk about “discovering” or “naming” minerals, it’s important to keep in mind that those minerals may have been discovered and even named—with some kind of name, even a special grunting sound—long ago in different places by prehistoric humans, migrating people, indigenous (native) people, or earlier civilizations.

Today, what we mean by discovering a mineral is that someone finds a mineral somewhere, a scientist tests the mineral to figure out its exact formula and structure, and people check a list to see if that mineral has already been discovered and named. If it hasn’t, then a scientist gives it a name, and it gets added to the list. Along with the name, scientists record where that new mineral was found, and they call that location the “type locality.”

But it could be that someone originally discovered the mineral thousands of years ago and may have even known it had special qualities and was different from other minerals. We just don’t know if that’s the case, because they didn’t write about it in a book, or carve it in runes, or draw it in hieroglyphs!

Of course, between the primitive time of prehistoric humans and the very modern time of today’s way of naming minerals, there was plenty of time where people could name and write about minerals but in a less scientific way. And, as a result, for the more common minerals, we have names that have been used for a long time and are often a bit easier to say, spell, and remember than the newest names.

What we mean on this website when we say a mineral was “officially” discovered can mean one of two things. First, it can mean when someone first identified it and wrote about it in a book, on an ancient scroll, or maybe even on a clay tablet. Or, second, it can mean when it was found and then confirmed using today’s sophisticated scientific process. Sadly for prehistoric humans, we don’t count their discoveries.

Kunzite fits our last category. As you may know, some rich and famous people love to have things named after them. Well, back in the 1800s, miners found a great source of tourmaline and other gemstones up in the hills of Pala, California. Their find was so famous that the Empress of China heard about it and bought up as much of their pink tourmaline as she could. (She loved pink tourmaline.) But another famous person was very interested in the find: George Kunz, who was vice president of the biggest American jewelry company, Tiffany Jewelers. And when a new pink/purple gemstone was discovered there, it was named “kunzite” after him. I don’t know about you, but if I had been the Empress of China, I would have been offended! So, finally, our last “ite” mineral name might have the meaning “the mineral that we hope Kunz’s jewelry company will buy lots of.”

© Kevin Downey/Well-Arranged Molecules

Not all mineral names end in “ite,” but all minerals have some history to them and some logic (or, sometimes, a mistake) to how they were named. The important thing to know here is that the name of a mineral can often tell you something about it. If you learn that someone’s name is Bob, it doesn’t tell you much, but if you learn that a mineral’s name is, say, purpurite, hey, surprise, it happens to be purple!

Which Mineral Is It?

Classes, formulas, and names are fine and dandy if you know what mineral you have, but what if you don’t? How can you tell which mineral you’re holding in your hand? A lot of different clues can help you to figure out what you have, and on each of the mineral card pages, we’ve included some of the most important clues.

The Mohs (not Moe’s) Hardness Scale

One clue we use to identify a mineral is how hard it is. For most minerals, if you find different pieces of the same mineral in different places, they will all be about the same hardness. In the early 1800s, a scientist named Friedrich Mohs who knew this decided to set up a scale of 1 to 10 to rate how hard different minerals were. Since diamond was the hardest mineral, Mohs gave it a 10. Talc, on the other hand, was the softest, so it only got a 1. All the other minerals, including later discoveries, were given ratings in between.

John Sobolewski (JSS), Talc-427985, CC BY 3.0

Some minerals on the soft side included gypsum, calcite, and fluorite, at 2, 3, and 4, while harder ones included quartz, topaz, and corundum, at 7, 8, and 9.

How did Mohs know which minerals were harder and softer? He used what’s called “the scratch test.” Basically, you can tell if one mineral is harder than another by using one to try to scratch the other. The one that makes a scratch is harder, the one that gets scratched is softer. So a diamond can scratch all of the other minerals, gypsum can scratch talc and maybe soft graphite, and talc can’t scratch any other minerals.

If you want to do a scratch test yourself, you won’t always have minerals with ten different hardnesses lying around—for example, diamonds—but fortunately some other common things have a known hardness or hardness range that can help. Here are some examples: your fingernail=2 to 2.5, pre-1982 U.S. penny=3 to 3.5, stiff copper wire=3 to 3.5, window glass=5.5, steel nail=5 to 7. Using these things to test a mineral can give you a rough idea of its hardness, which can help you get closer to figuring out what it is.

Of course, if you have a mineral specimen you like, you don’t want to scratch it in some obvious way, so it’s best to find a part that’s hidden or chipped/scratched already to do your testing, or use a chunk of the same mineral that you don’t want to keep.

Specific Gravity

Normally when we talk about how heavy or light something is, we talk about its weight, and weight is what the numbers say when you step on a scale. But several other words can be used, especially by scientists. As you may know, gravity is the main thing that keeps us standing on the ground instead of floating around. But what is specific gravity, and why is it important? And what about density? Well, this can easily get confusing, but let’s see if we can figure it out.

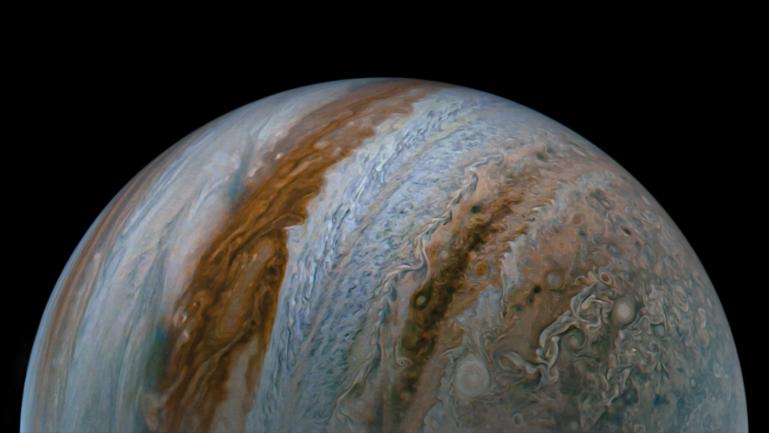

You may know from science class, science fiction movies, etc., that gravity is different on different sized planets and moons. Since we live on Earth, that’s our standard for gravity, but you may have heard that if you’re on the moon, there isn’t as much gravity, and on huge Jupiter, there’s much more gravity. Wherever you are, your “weight” isn’t just you, it’s you times the amount of gravity.

Say you have a dog, and the vet says it weighs 35 pounds. That’s its Earth weight. On the moon, where there’s much less gravity, your dog would weigh about 6 pounds, but on Jupiter, your dog would weigh almost 83 pounds! So your moon dog would be jumping around and practically flying, while your Jupiter dog would probably just lay there looking sad.

Photo: © NASA. Image data: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS; Image processing by Tanya Oleksuik CC BY NC SA 3.0

Another way to compare the heaviness of things is to talk about their density. To put it simply, how dense something is means how loosely or tightly packed it is. For example, in a bag of popped popcorn, the popcorn is pretty loose, but if you fill the bag with sand instead, the sand packs together tightly, so it has a higher density, and it will feel much heavier. For all rocks and for minerals that are made up of more than one element (so, not diamonds, gold, etc.), their density is how packed together their molecules are. For most minerals made up of only one element, their density is how packed together their atoms are.

You may have heard that lead can protect you from radiation, and that it’s very heavy. The reason for both of those things is that it’s really dense!

Although popcorn and sand are solids, everything on Earth has a density, including gases and liquids. Kind of like Mohs hardness scale, where Mohs picked the common mineral talc to give the number 1, scientists decided to use the density of water to create the measurement called specific gravity and gave water the number 1. Water is the most common liquid and one of the most common things on Earth, so it was a natural choice. It’s also handy to know that if something’s specific gravity is below 1, it will float, and if it’s above 1, it will sink! And that’s another main reason why they picked water.

Once they had that measurement for water, they could compare the density of other things to the density of water to get their specific gravity. They didn’t give specific gravity a unit—like pounds, or ounces, or kilos—but it wouldn’t be wrong to think of the unit as “waters.”

As you’ll see on each mineral page, minerals can have very different specific gravities. Sodalite’s specific gravity is pretty low, around 2.3, while the specific gravity of the lead-based mineral galena is 7.60—do not build a boat out of galena.

Okay, but, really, how is specific gravity useful? Well, if you have a mineral, and you don’t know what it is, if you can figure out its specific gravity, you can really narrow down what it might be. How do you figure out the specific gravity of a mystery mineral? Well, the classic method used a balance scale, a glass beaker of water, etc., and it was kind of complicated. But there’s an easier way to do it, and a wise rock collector, John Betts, tells you all about it on a page on his website called The Betts Method. The one special thing you’ll need to use this method is a small digital scale.

Specific gravity can be a handy thing to know, but sometimes you can’t use it. If you have a mineral, but it’s attached to a rock or has other minerals stuck together in the same piece, you can’t measure the specific gravity of just the mineral you want. Instead, you’d get the specific gravity of the combination of your mineral and the rock or your mineral and the other minerals. Also, because you do have to dip the mineral in water, you wouldn’t want to do this test if your mineral might be halite, because it would melt! Well, it’s a helpful measurement, but it’s not perfect.

Shape

If you’re a rockhound and you go looking for rocks and minerals outdoors, they aren’t always just sitting on the surface waiting for you, sometimes you have to dig for them, and that means sometimes they’re dirty. And when they’re dirty, it’s hard to tell what they are.

One thing that pro rockhounds do is just watch for anything that has a crystal shape, like a perfectly straight line or a square or hexagon with straight edges. They know if they find something with straight edges, instead of having jagged edges or just looking like a lump, it might be a crystal or part of one. They keep those pieces, then wash them off later so they can see the color, how shiny they are, etc.

An example of a mineral that often has hexagon-shaped crystals is aquamarine, a type of beryl. So if you’re digging somewhere people have said you might find aquamarine, and you find a piece of a hexagon-shaped mineral in the dirt…“A-ha, this might be aquamarine!” Definitely keep that piece.

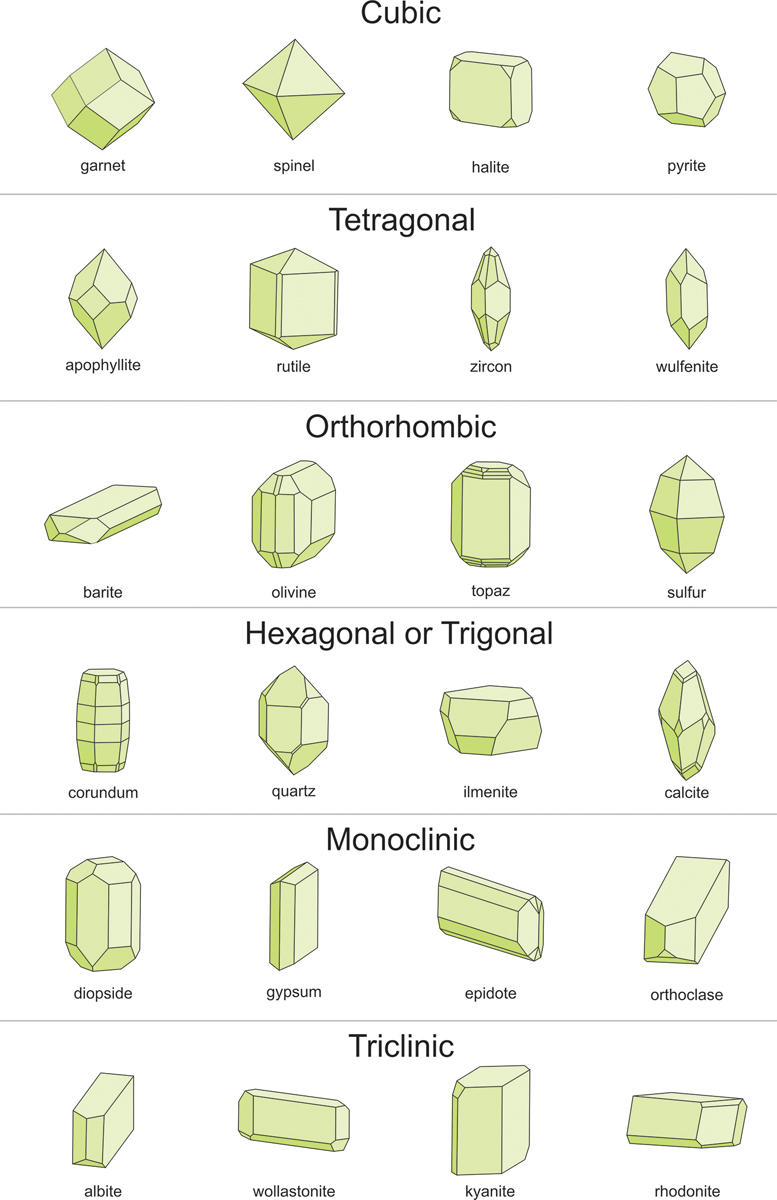

You’ll see in the information for aquamarine that its official shape is “hexagonal,” or scientists would say it’s “in the hexagonal system.” There are seven crystal systems, and all minerals fit one of the systems. It can sometimes help to know the crystal system, like with aquamarine, but they can get really confusing really fast, and sometimes they don’t seem to fit.

Pyrite, or fool’s gold, is a good example. It’s in the isometric system—easy, right? No, what’s “isometric”? Well, the most simple version is a cube. “Oh, okay, I know what a cube is,” right? And when you see a piece of pyrite from Navajun, Spain—where the pyrite comes in big, perfect cubes—it’s easy to tell it’s a cube and it’s pyrite. But pyrite comes in another shape that has 12 sides called either a dodecahedron (dodeca means 12) or, sometimes, a “pyritohedron.” That 12-sided version of pyrite is common enough that they named a shape after it!

Twelve sides is definitely not the same as a cube (six sides), but it’s still officially in the isometric system—go figure! And when you look at the other systems, which almost all have names as confusing as “isometric,” they also have all sorts of complicated shapes that you wouldn’t think would fit (as you can see in the figure below). Just so you’re familiar with them, here’s a list of the systems:

- Isometric (Lucky for us, some mineralogists just call this “Cubic”!)

- Hexagonal (Some mineralogists combine Hexagonal and Trigonal into one system.)

- Trigonal (See Hexagonal.)

- Tetragonal

- Orthorhombic

- Monoclinic

- Triclinic

Source: Dexter Perkins, Mineralogy, CC BY-SA 4.0

Now, if you decide you want to be a mineralogist or gemologist, you’ll want to memorize all of the systems, but if you just want to be a rockhound or collect minerals for fun, the best thing is to get used to what different minerals look like. For example, yes, pyrite is often square-shaped, and so are galena and fluorite—and fortunately they’re gold-, gray-, and, well, candy-colored, so it’s easy to tell them apart. Other minerals are usually kind of flat, some are usually very pointy, some are usually shaped like a sword, and others are usually ball shaped. If you get used to watching for those shapes, those will be much easier to remember than the systems.

Habit and Form

Before we move on to color, let’s talk about a couple other shape-related terms. As noted, on this website we talk about shape rather than “crystal system,” but you may hear other words that are also related to shape, such as habit and form. It’s good to know what they might mean when different people use them so you don’t get totally confused.

Habit has to do with the overall shape of how a mineral commonly occurs. The graphic below shows a number of the most common habits that minerals can form in.

How is habit different from plain old “shape”? Plain old shape would say copper is isometric, a cube for example. So if you have one crystal of copper, it’s likely to just be a cube. But usually you don’t find one crystal of copper. Copper likes to crystallize in these cool branching shapes called dendrites that can be made up of a bunch of cubes connected together. When we find a specimen that’s grown in branches like that, we call that group of crystals its habit, and that habit is called dendritic. But, and this is a big but, some things have a habit that’s pretty much the same as their shape. For example, as mentioned earlier, pyrite is perfectly happy just forming a single cube sometimes, so that can be its shape and its habit.

It’s important to note that one habit that’s really common for rocks and not that uncommon for minerals is “massive.” When a rock or mineral has a massive habit, it doesn’t form in a definite special shape and isn’t made of a bunch of organized crystals, it’s just a solid mass.

We probably won’t mention “form” anywhere else but here, but here’s the scoop: Depending on who you talk to and how specific they’re being, mineralogists might say that a mineral’s form is the same thing as its shape, a cube for example, or they may refer to form as the shape of just one face of a crystal, like a square that’s one face of the cube. Having the same word possibly mean two different things is not very helpful! As a result, we’ve decided to helpfully not use this term when describing minerals’ shapes. When we do talk about “forming,” we just mean “create” or “become,” like flour, sugar, baking powder, butter, and eggs mixed together form cookie dough, or a halite crystal forms when you evaporate salty water.

Color

Thank goodness for color—finally something easy to understand! We’ve all heard of many different colors, and a lot of the color names are pretty standard. And with some minerals, color is a really helpful way to identify them. Then again, with others…not so much.

If you’ve seen any minerals from Colorado, you may have seen beautiful specimens that include smoky quartz and amazonite together. Both of those minerals have very reliable colors. Smoky quartz is always dark gray to black, and amazonite is always light blue-green to dark blue-green. So if you’re looking somewhere those minerals have been found, you’ll probably know if you’ve found them by their color.

On the other hand, apatite can be found in a wide range of different colors. The most valuable apatites are a deep purple color, but you can also find them in yellow, green, blue, pink, red, and gray. So if you find a chunk of a mineral, and all you know is its color because it doesn’t have any crystal edges and you haven’t tested it, it might be hard to say whether it was apatite or something else.

On the other other hand, as with shape and looking for crystal edges, finding any color at all can be a good sign. If you’re digging in the dirt or sand, and most of the stuff you find is gray or brown, but you see a bright-colored mineral, that’s very helpful! You should keep that mineral, then figure out later what it is.

Luster

When gemologists want to be scientific about how shiny a gem or mineral is, they talk about its “refractive index.” When mineralogists talk about the same thing, they call it “luster.”

Mineralogists use a number of different words and fancy names to describe the luster of different minerals, and some of them are right on the line between luster and another way to describe minerals: sheen. (See “The Essence of “-escence”” below.) Here’s a list of the most common words, from most shiny to least shiny. Note that some minerals can look like both a metal and a nonmetal, such as rutile.

Metals:

- Metallic—Shines like metal with no tarnish on it, sometimes like a mirror

- Submetallic—Shines in a silvery way, with some tarnish or the texture of the metal making it less bright

Nonmetals:

- Adamantine—Very bright shine, like a faceted diamond has

- Vitreous—As shiny as glass (vitreous=glassy)

- Resinous—Slightly less shiny but still pretty translucent, like resin (pure tree sap) or amber

- Pearly—Shines a little bit and a little translucent, like a pearl

- Greasy/oily–Looks shiny like it has grease or oil on it

- Silky—Shines a little bit, like silk or satin, and shows what looks like very fine lines inside its shine

- Waxy—Shows a slight glow when you shine a light on it, just a little translucent

- Dull—No shine or glow, opaque

- Earthy—Grainy, like rust or dirt

Sheen: The Essence of “‑escence”

Along with luster, some gemologists or mineralogists get a little dreamy and start talking about “sheen” as another way to identify minerals that’s kind of like luster…or maybe even the luster of the luster. When you read the science information for the minerals on the Rock Readers site, you’ll see some words that are used for the special sheen that some minerals have. What a lot of the words have in common is that they end with “‑escence.” (The ‘-’ means it’s a suffix, which is letters added to the end of a word.)

You might be able to tell by how we described the different levels of luster or shininess that they’re not very easy to describe! Now take that difficulty and quadruple it to get how hard it is to describe a mineral’s sheen. Instead of coming up with complicated descriptions, gemologists/mineralogists decided to just name the special sheens after the minerals that had them. If you find another mineral that has a similar sheen, you basically just say “It looks like this other mineral’s sheen.”

Here’s a fairly complete list of “‑escences,” though there are probably more!

- Adularescence–Like the feldspar variety called adularia

- Aventurescence–Like the quartz variety called aventurine

- Fluorescence–Like fluorite, though this is not exactly a sheen

- Labradorescence–Like the feldspar variety called labradorite

- Opalescence–Like opal

- Pearlescence–Like pearls

Where did the “‑escence” idea come from? Well, before all these other “‑escences” came along, we had the original, “iridescence.” Iridescence comes from the Latin word for rainbow, and it refers to that rainbow-like shininess you can see when, for example, oil or gas floats on water. (The same Latin word is the source of “iris,” which is the colored part of our eyes.) A lot of the other “‑escences” are just different kinds of iridescence.

Not to be left out, we should mention that there’s also at least one “‑ant,” with the most popular being “chatoyant.” What does that mean? It means “like a cat’s eye,” and you’ll hear people use it to describe all sorts of cool visual effects in minerals, whether they really look like a cat’s eye or not!

Streak

Streak refers to what color line a mineral leaves when you scrape it along a piece of unglazed tile, which is called a “streak test.” Most pieces of the same mineral will leave the same-colored line, so if you can test your mineral’s streak color, you can see if the color you get matches any mineral’s standard streak color. Although not every streak color is unique–for example, you’ll notice that a lot of minerals leave white streaks, including pretty much anything that’s made of quartz–knowing the streak color of your mineral may help you narrow down the possibilities.

You can also use a streak test to tell some minerals apart. For example, if you have an iron mineral piece, and you want to know if it’s hematite or pyrite, the hematite will leave a deep red streak, and the pyrite will leave a greenish-black streak.

A streak test is pretty easy to do and can be helpful. The only real challenge is finding a piece of tile that’s white and has a rough surface. If you’re lucky, on some tiles, the back side is that way, even if the front is glossy or a different color. If you can’t find the right kind of tile, you can order what’s called a “streak plate” online from science stores.

As with the scratch test, you have to be willing to damage your piece of mineral a little, so use a hidden or rough part of your mineral, or use an extra piece of it you don’t need, if you have one. But if you can get the right kind of tile and can find a part of your mineral you don’t mind scraping on it, you can use this test to help you identify your mystery mineral.

Other Things (cleavage, fracture, etc.)

If you have a guidebook for rocks and minerals, or if you use the Mindat website or other Internet rock/mineral resources, you may have seen other information that people use to identify minerals. Other qualities include cleavage, fracture, etc.

Cleavage and fracture both refer to what happens when a piece of a mineral is broken, but in two different ways. It’s easy to confuse the two, and even when you understand both, they’re helpful for some minerals, but not for others. If you’re curious about those characteristics, you can find out more using other mineral resources, including websites we’ve recommended and mineral field guides/nature guides/handbooks.

Finally, there’s another test that scientists used to do called a “bead test,” that’s even more complicated, and involves using the chemical borax, a blow torch, and, ideally, a piece of platinum–one of the most expensive minerals in existence. To perform this test, you melt a tiny ball from powdered pieces of a mineral, combined with borax, on top of the piece of platinum, using the blow torch. It’s definitely a “mad scientist” kind of test! Well, as you can imagine, we decided it wasn’t worth providing the blow-torch-melted bead information for the minerals. Very few people will ever do that kind of test!

Note: All uncredited photos this page © Carl Quesnel